Shutterstock

Crissle has built quite a name for herself over the last few years. From her Twitter presence to her thoughts on the podcast “The Read,” which she shares with Kid Fury, to her seat on the panel of MTV2’s “Uncommon Sense,” Crissle is known for her opinions. From her love of Beyoncé to the way she rides for Black women, she is that girl. One of my favorite moments from her came when she read this White man for filth after he suggested she was overreacting for disliking Sarah Silverman’s Blackface.

Late last year, we named Crissle one of the people we wish were our friends. She’s just that cool, really.

But none of us get it right 100 percent of the time. And last night, our beloved Crissle found herself making some controversial comments about biracial children.

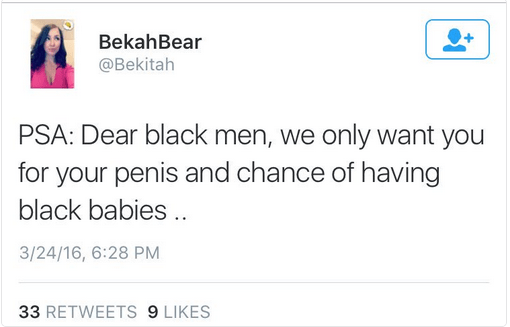

It all started with a screenshot of a tweet from a White woman who wrote:

Source: Twitter

Someone suggested the Crissle “finish” the woman who tweeted this. But she declined, referencing the fact that far too often Black men don’t come to our defense.

I meeeeeaaaan, facts. The rider-ship is not reciprocal.

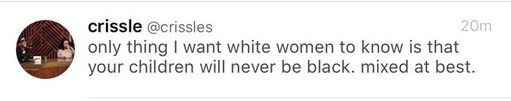

But things took a left turn when Crissle tweeted about White women and the children born from their interracial unions.

Source: Twitter

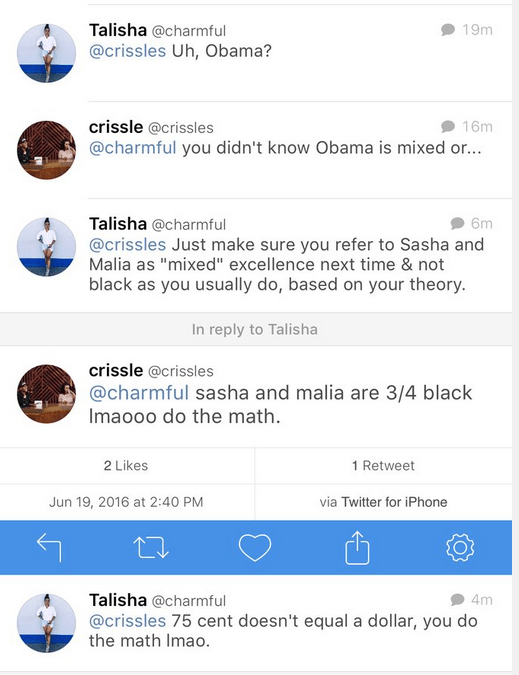

And the clapback was swift.

Source: Twitter

Crissle went back and forth with several people throughout the night talking about mixed-people privilege, our current definition of Blackness being deeply rooted in slavery and racism and more. And while she brought up these valid points, and even deleted the original tweet, the statement was just flagrantly wrong.

I know how Black women feel watching Black men go out of their way to choose White women, diss, dismissing, stepping on or over us in the process. I’ve seen it far too many times to ignore. And I’m not talking about the celebrity realm. I’m talking about everyday, ordinary Black men, bashing everyday, ordinary Black women. I know it’s real. And I even agree that Black men don’t support us in the ways they should. Issues that are specific to Black women are either diminished or completely disregarded. So I can understand a Black woman choosing to opt out of caping for Black men.

I even understand the biracial children enjoy a different type of privilege than other Black people. Biracial kids, children who are Black and White, are believed to have the ideal hair texture. They’re often the children we see as child stars. I remember when I was growing up, there was the very prevalent belief that biracial children were prettier than Black children. There was a time, as a young girl, where I actually believed that. I thought that God made biracial children beautiful as a way to encourage Black and White people to get over their centuries-long beef and come together. Literally and figuratively. Now, I recognize that the fetishization and uplifting of these biracial children is really just a thinly masked attempt to belittle Blackness. The sentiment is that one needs European ancestry to appear more attractive. We’re attractive all on our own.

I get Crissle being mad at White women who actively and specifically seek out Black men, trying to live out some type of sexual fantasy or piss their parents off.

There is a whole lot of truth in the fact that the lines we’ve drawn around Blackness, in this particular country, are rooted in slavery. There are actual codes, from the 1600s that dictated how children born of a slave and free person, one most likely Black and the other White, were to be treated. They were called Code Noir, a decree passed by the French King, was adopted in the West Indies, in some South American countries and in some Southern states in America, most notably Mississippi and Louisiana.

And in those codes, meant to control the economic labor of White people and protect their assets, the authors of these codes wrote, “Children between a male slave and a free woman were free; children between a female slave and a free man were slaves.”

We all know that after the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, Black, outside the continent of Africa, was often synonymous with “slave” and White was synonymous with free. And Crissle was trying to argue that our very definitions of Blackness comes from that system. They were set in place so that White men who raped their slaves could still maintain, not only their resources— in not having to include these Black children in their will—but also their work force. If your child was, by law, your slave, you could deal with him/her however you chose.

Still, we could also argue that her refusal to see the children of White women as Black is also a result of those very same codes.

Yes, Crissle. Blame Black men for the way they’ve denigrated their own kind. Blame White women for the hyper-sexualization of our men. But I got lost when we started talking about the children. They were born, not understanding society’s construction of race and the implications of their identity. You know, tabula rasa. Whether a child is born because of rape, or two consenting adults having sex, the child has nothing to do, at least in the beginning, with those racial politics. And ultimately this same child will have to decide for him or herself how they will be identified.

Furthermore, if a biracial child chooses to identify as Black, I can’t imagine how that poses a threat to our own identity as “just Black.” How does isolating this many people help to illuminate the issues of our struggle for equality? How does embracing children with a White mother and Black father as Black pose a threat to Black women or the unity of Black men and women? Really, who does this help? Perhaps the statement was directed toward White women specifically and just so happened to directly impact another group.

But more importantly than this, I wonder where do we draw the line? Anyone from the diaspora is very likely not 100 percent Black. Based on Crissle’s standard, many of the biracial children who were forced into slavery, despite having a White parent, wouldn’t be Black, though they certainly lived the Black experience. Not only that, so many of the historical figures who we praise, who identified as Black, were also biracial. Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, some of the wokest Black men of their time, some of the men who helped liberate and empower thousands of other Black folk, were biracial. We have to ask ourselves, where would we be if biracial Black people hadn’t chosen to identify with us and fight to bring awareness to our struggle? Are we going to pretend that Jesse Williams, with his light brown skin and blue eyes, is not one of the loudest voices in entertainment, fighting for our equality?

Again, biracial Black folk enjoy a level of privilege, but still they experience oppression and ostracism. So many biracial children feel like they have to choose between being Black or White. They feel like they don’t fit in with one group or the other, or both. And if a biracial child is in a room full of White people, as so many Black folk so often are, they’re still other. And in many instances, will be treated as such.

Honestly, I struggled about whether or not to write this. I saw the ways in which people tried to attack Crissle personally for expressing her opinion. They said she was mean and nasty. One person even alleged that “The Read” would be so much better without her. Truth is, “The Read,” has never been done without her. Honestly, I’m not here for another game of attack the opinionated Black woman. It’s tired.

And in Crissle’s defense, she ultimately realized that some conversations aren’t for Twitter and admitted “God ain’t finished working on me etc etc.”

I decided to ultimately write this because she is not alone in this school of thought. Increasingly I’ve noticed that Black people, on social media, in person, etc, are calling biracial people “not Black.” And I’m really wondering when this became a thing. Black people have always embraced biracial people as one of our own. When did this change? When did biracial people become excluded from Blackness? And I’m not asking that rhetorically, if someone has an answer, do share.

When I went to Ghana, during my junior year of college, I was hurt to learn how some of the people regarded me. I’m sure I told this story on MadameNoire before, but this artist, who I had just supported by buying some of his work, told me that I wasn’t Black. He nailed the point home by holding up his arm, next to mine, noting the difference in skin color. “Something happened in between here and here,” he said pointing to his arm and then pointing to mine.

Hell yeah something happened.

My ancestors, some of them from that very country, unwilling crossed an ocean. And after that, or hell, even on the journey, my female ancestors were raped. And some of them bore children. That’s what happened from his arm to mine. But just because someone literally forced their way into my family tree and genetic makeup, it doesn’t mean that I’m not Black.

And what I learned from that ordeal is that no one can tell you how to identify yourself. They don’t know what happened from one generation to the next. They don’t know the circumstances that led to your birth or the circumstances that led you to identify in the way you do. The work of self identifying is for us all to do individually. And it’s our job to hold on to our choice, despite what others may say about it. At the end of the day, Blackness is too broad to be boxed in.