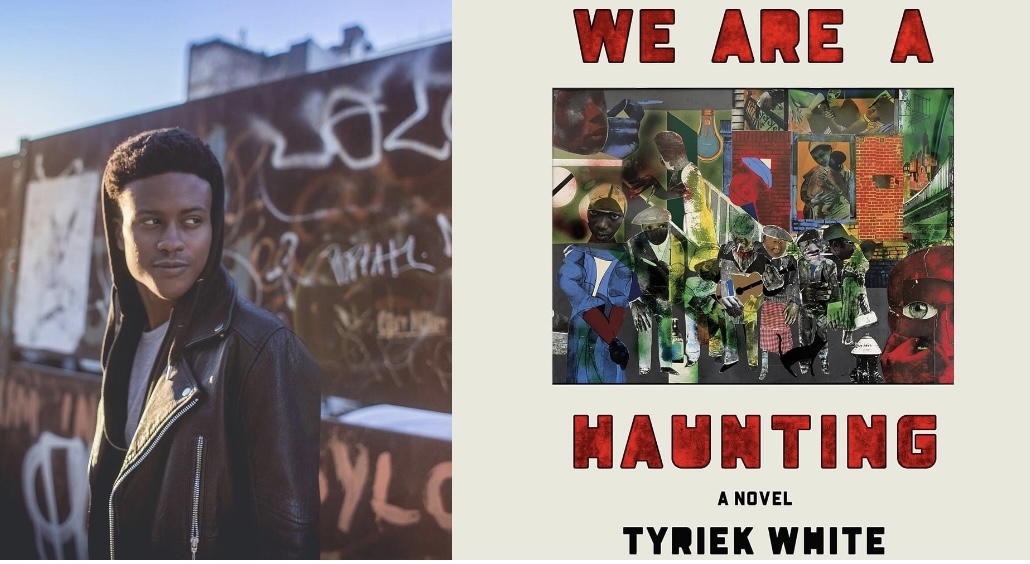

Source: Courtesy of Tyriek White / TW

Tyriek Reshawn White is a talented writer, musician, and educator born and raised in Brooklyn, NY. He studied Africana Studies and Creative Writing at Pitzer College, and recently earned a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Mississippi. We Are a Haunting is a poetic and beautiful debut that has been described by MacArthur Fellow Jacqueline Woodson as “a beautiful, haunting and hued narrative of American living,” and praised by MacArthur Fellow Kiese Laymon as a novel that is “so New York—so, so New York—yet so deeply southern on lower frequencies. It’s astonishing.”

We Are a Haunting will be published on April 25, 2023 and can be ordered on Penguin Random House website. Tyriek White sat down with MADAMENOIRE to talk about his debut novel and how Mississippi influenced his writing process.

MN: How does it feel to have a debut novel coming out into the world, especially one that is being compared to the writing of such esteemed authors like Jesmyn Ward and Jamel Brinkley?

TYRIEK WHITE: It’s amazing to me. You know, these are writers that I’ve wanted to be in conversation with, you know, for my entire life. Them and Baldwin, Morrison…it’s sort of what I was writing to all this time. This story of working-class Black people has been told in many ways. But I wanted to tell it in a certain way that talks back to those greats, that talks with my peers. I’m just excited. I’m hype.

Awesome. So, speaking of the focus on working-class folks, the novel tackles various social issues that plague the characters and the people around them. Why is it important that we are focused on these particular characters in Brooklyn?

The story is about this young man and his mom, and this conversation that they have across time, death, and space. At the core of all these structural systemic imbalances that affect us is this relationship between a mother and son and how that feeds into each other. It’s also this family saga. But it really is about that generational connection that happens when I wear the pain and the joys of my ancestors, my mother, and my grandmother. Those things are intrinsically within me. So, writing a story about these three generations of a family who are from the South and who migrated to Brooklyn, that story within itself is rich with historical, social, and political implications. These things are just inherent. ​​But I hope people listen to the characters and understand how they go about maybe finding healing. Or what does a mother tell their son about healing? How does the mother tell their son about loss and healing when they’re not there? What does that conversation look like? I was interested in that.

Can you tell us a bit more about the importance of ancestors in the novel and why it was important to incorporate it in the ways that you did?

I think narratively it worked because when you’re writing about how the implications of the past affect what we do in the present, I think it worked the most naturally in explaining that or showing that on a spiritual basis. It’s very important to myself, to Key, to Audrey. Especially with Audrey. There’s that Western Christianity that we all know and experience growing up, but I think Key troubles that a bit because she’s able to physically go back into the past or, or see remnants or artifacts from the past and she has to engage with that. So that troubles this Western idea of spirituality. She sees ancestors everywhere. So when it comes down to Colly, it’s like he has these understandings of these kinds of ideas of spirituality. That’s really the conversation that he’s dealing with.

Mmm…yes.

Especially because I see a lot of talk about how honoring your ancestors or their traditions is seen as demonic because it’s not this Christian thing. And it’s like, no, no, these are the things that our people, our family, and our ancestors believed, you know? So, I really wanted to have that conversation.

Right. And in certain instances, it’s part of why we got free as enslaved people who were dropped off in different parts of the world. Our spiritual traditions were important. So I think it’s really interesting to explore that in a novel and what that looks like…

A lot of it is inherent. And sort of the “Christian things” that we do, the ways that we worship, the ways that we show ritual, the ways that we send off our dead…all of these things, we might think are Christian, but it’s really connected to what’s passed down from our African ancestors. Even the ways that we engage in ritual and the ways that we gather.

Can you tell us a bit more about what inspired the syncretic nature of Colly juggling Western Christianity and African Traditional Religious spiritualities in the novel?

The inspiration comes from the story of the Flying Africans. When we first meet her, Key tells us about the flying Africans, who flew back to Africa after being kidnapped to be brought here. It’s a story that a lot of our texts deal with. Toni Morrison’s novel Song of Solomon includes it. There’s an emphasis on return. There’s an emphasis on restoring. And these are our folktales, the stories, and myths that we established for ourselves. So it all started at that spiritual center. And then it grew to all the ways we practice African spiritualities, and how it follows us through imperialism and colonialism. It follows us through the slave trade. So you get Voudun in Haiti, you get Santeria in Cuba and Latin America, and other syncretic religions. And Key is operating like a modern-day Orisha. She’s in this hood, but she’s helping people. People are coming up to her, to speak to loved ones. People are coming to her to help them to establish a connection with people they’ve lost and people who aren’t here yet with her being a doula. So I thought it was interesting to play that over especially, with the environment.

Right. With her living in the hood…

And when you think about the hood, or when you think about working-class neighborhoods you don’t think of this like Orisha or this healer or, this person navigating that space.

So, I noticed how much nature imagery was featured in the novel, and almost felt like it was a lens through which some of the characters saw the world. We also saw how the characters tended to a garden in the text, and one typically might not think about nature when they first think about East New York, Brooklyn. So, can you talk to us a little bit about how nature emerged in your writing process?

Being in the South and being in Mississippi while writing a good majority of this novel, reinvented how I wanted people to experience East New York and how I wanted to write about it. It definitely affected how I wanted to write about it. And East New York itself… I don’t think many people would think about gardens, or think of it as a site that’s like an environmental watershed. East New York is on marshland. At the southern tip, there is a lot of marsh and a lot of swamp. It used to be on landfill and it’s notorious for being one of the largest cases of landfill in New York City during the 70s and 80s. It wasn’t enough to just think about it in political and social terms. There’s also an environmental element and the disenfranchisement that happens in the community like East New York. It’s very environmental. You have a neighborhood filled with factories, old heating plants, reservoirs, sewage stations. You have to think about it as a bodily experience. And how do you convey that it acts on the body? It’s not just people who deny you an apartment or the people who deny you at the bank, or the people who give you food stamps. How does it affect how you breathe? How does it affect the way you move about the world? And I think it’s finding new ways to talk about this urban grit environment to give the reader the impression that this weighs on your shoulders. But on the flip side as well, just like having Colly interact with nature, you know? And having him go into the water or just how he moves through the world. It’s a different way of talking about how New Yorkers and others who live in urban environments move through those spaces.

That made me think about the Igbo Landing aspect of the novel. Can you tell us about how this modern-day story is connected to that historical site and the historical event associated with it?

It goes back to the idea of return and restore. Audrey would tell Key the story of Igbo Landing. And Key would have a similar experience of being at the shore and wondering what a restoration for Black Americans would look like. It had a lot to do with Orlando Patterson’s idea of social death. So, slavery and the post-manifestation of it, like the prison industrial complex. Slavery was a social and political death. So how does that change someone’s experience in the world? So the whole thing was like how do I talk about the experience of Black people in this nation who are experiencing a social death or other metaphoric death in terms of how we are treated and the rights we are given. I wanted to connect that with the idea of people who were kidnapped from Africa being brought here and then rebelling. And then having this path that led them back home, whether it was through flying or swimming. And when you think about the scholarship of someone like Saidiya Hartman, you could ask the question of whether that is even possible or does that even exist in the same ways? This book is asking those questions. It is and it can be, but how do we figure out other ways for us to figure out what that return home is for us? I don’t have the answers but I put all of those ideas in conversation.

Well that leads me to my last question, why is this book important right now in this moment in time?

Firstly, I think in terms of ancestral veneration, more people are looking to other forms of fulfillment and healing in terms of spirituality and even working that into their Christianity. I mean, I do it. Secondly, I think the importance of this idea of how we can look to the past to inform our future or inform our present. I think that’s extremely important now because they’re trying to get our history up out of there. They’re trying to change our entire narrative. You think about the 1619 Project and how there was extreme backlash against that. You think about how they’re banning books everywhere. I double majored in Africana Studies and English, and half of what I majored in is banned illegal in some school systems. That’s wild. That’s a wild to think about.

They trying to disappear us…

They trying to disappear us. You feel me? I think we have to be super proactive and super precious with what we have. We know this country runs off what we did to us. So, we can’t let them skew that narrative. So, we have to return and to restore. That’s it. That’s really it.

RELATED CONTENT: ‘One Blood’: Author Denene Millner Shares New Novel, Tasty Excerpt And Book Cover Reveal