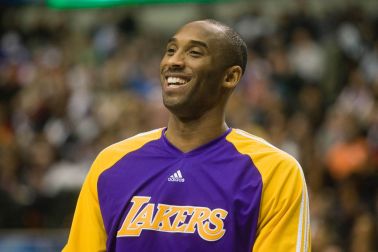

Source: Anadolu Agency / Getty

In the wake of the death of NBA superstar Kobe Bryant and his 13-year-old daughter Gianna, the last few days, to say the least, have been dark. Not only in the sports world, but within the Black community. On Sunday, January 26, although controversial in some respects, we lost a symbol of Black excellence, a coach and for some, a father figure. Since his untimely death, Black men in particular have not been shy about sharing their grief.

“We’re all Lakers today,” said Glenn Anton “Doc” Rivers through tears, a former player and who is currently the head coach for the Los Angeles Clippers. “The news is just devastating to everybody who knew him — have known him a long time. You know he means a lot to me, obviously…He had that DNA that very few athletes can ever have — the Tiger Woods, the Michael Jordans. I was getting to know him since he retired. This is a tough one.”

Shaquille O’Neal also shared his pain, during a television special honoring Bryant. The two played together for the Los Angeles Lakers and won three championship rings from 2000-2002.

“I didn’t want to believe it. And then … everybody called me, and we found it was confirmed,” said O’Neal. “I haven’t felt a pain that sharp in a while.”

Players openly cried for Bryant and struggled to hold it together to play their scheduled games. LA was so broken, the Clippers and Lakers game that was scheduled for January 28 was postponed. The NBA acknowledged their players’ pain and gave them time to heal. It’s important we understand that pain like this exists outside of death as well. Culture and the traditional ideas that circle around what it means to be a man or woman affect how we view mental health treatment.

It may sound odd, but seeing Black men cry and show despair on television is as important as Kobe Bryant’s legacy. One of the first posters in my little brother’s room was of Bryant, which my father purchased for him. Although my household outranked the boys by 3 to 2, my mother, sister and I were still forced to watch the now-classic games Bryant dominated, revealing why he is truly a legend. Because of that, despite my disinterest in basketball, I grew up with Bryant too.

When my brother first heard the news, he demanded I vet my sources, and once the news was verified he didn’t have much to say.

“This is so sad, and out of nowhere,” he said. “Like how does that even happen… it’s a lot. Like it’s wild to say he died like that…I feel bad.” And with the shift of his hat, my brother didn’t say much else.

My father, ground zero of the love and resentment for basketball within our home, tried to remember a time he felt this startled by an athlete’s death. He spoke about Walter Payton, a Chicago Bears running back who died at age 45.

“This reminds me of Payton when he died of brain cancer…or when Tupac died,” he said. “This is real bad.”

Death is one of the few exceptions we allow men to openly express their emotions. And watching prominent figures express their grief unapologetically has a way of making other men feel validated, providing a pass to participate in sorrow. The aftermath of Bryant’s death is a hard and blatant reminder that it’s OK, to not be OK.

Minorities in the United States are less likely to seek mental health treatment, according to research published by The Commonwealth Fund. Only 66 percent of minority adults have a regular health care provider compared to 80 percent of white adults. Growing up, Black boys are taught being emotional is a level of weakness or femininity, or laden with homophobic ridicule. It’s in part because of dogma like this that Black men kill themselves by suicide 3.4 to 1 compared to Black women.

Once we unlearn these toxic hindrances, and accept that therapy and healing are crucial elements of growth and development, we create spaces to heal and literally save lives. As a community we are so shaken by Black men showing emotion that #BlackBoyJoy trended in 2016 encouraging positive imagery of Black boys and men on social media.

Black men have always been special. They have always needed permission to be emotional or vulnerable because, in our culture, there isn’t a lot of room for them to be completely human. They’re traditionally trapped behind aggressive tropes and expectations. Contrary to popular belief, Black men have always been emotional, but when you’re trained to suppress certain levels of certain emotions, it reveals itself through anger or numbness, which are also signs of depression.

In the words of Babe Ruth, “Heroes get remembered, but legends never die.” In a lot of ways, Bryant will live on, even if it’s not in an NBA logo. He’s ingrained in every basket you know you’ll make, whether via a trash can or a hoop.

The death of Bryant can teach us a lot of things; the value of life, family and what it means to leave a legacy. But in our grief, we should keep in mind what it means to take care of ourselves emotionally. His passing is a reminder to be open and how valuable and cathartic that energy is, even when it hurts.