Source: iOne Digital / Interactive One

Patrisse Cullors wants us to do better—by ourselves, of course, but most importantly by one another. Cullors is known for her revolutionary activism as the co-founder of Black Lives Matter and leading the charge with much needed radicalism at a time when Black Americans faced contemporary forms of oppression and systematic racism.

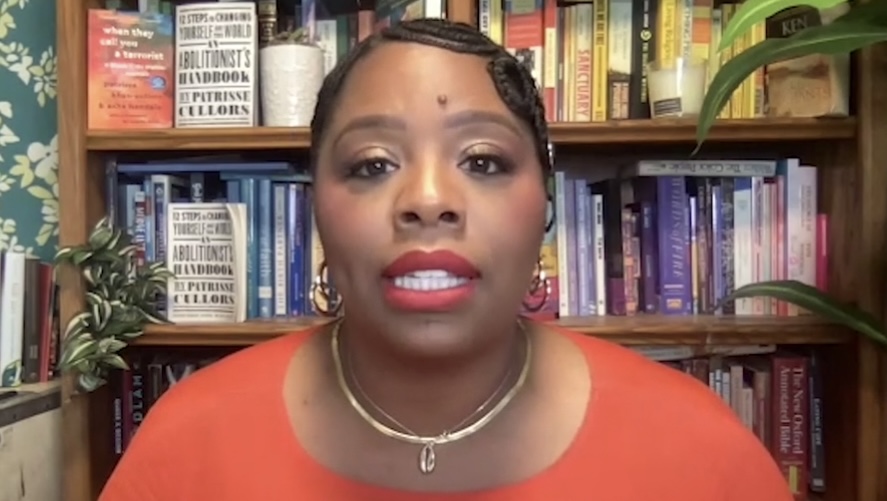

Having shaped an entire movement that demanded equity, justice and preservation for Black people, Cullors is a force to be reckoned with but also one who has established a blueprint for others to do the same. On Jan. 25, Cullors shared that strategy in her second book, Abolitionist’s Handbook: 12 Steps to Change Yourself and the World. The dedicated advocate sat with MADAMENOIRE on a segment of I GOT QUESTIONS to discuss this groundbreaking text.

MADAMENOIRE: Thank you. It’s so good to have you. It’s so good to have you. And I really want to preface our conversation with letting you know that I’m showing up as someone who is eager to learn all about the work you’re doing, all about the text. So don’t beat me up if I sound naive about something, but I got a question, and I hope you’re up for getting the answers/providing the answers. Abolitionist Handbook, lovely artwork… lovely work… I want to jump right in with the first paragraph and where you explain to us what a handbook is. Right. “What you are holding is not meant to live on a bookshelf. It’s not a textbook meant for a semester or some singular moment in time. It’s not meant to serve as a backdrop for a conference call. My goal is this. The things I’ve learned about the work I’m in can be valuable.” So, I’m going to be honest. When I first heard the title, I was like, this is a twelve-step program to how I can do better, be a better activist and advocate for people. But that’s not what this is. You gave a full ass disclaimer in the first paragraph. Right and you give real world examples. You give guiding questions throughout the text at the end of each chapter. And I feel like as a writer, that’s a craft move. So, what led you to kind of explore this format?

Patrisse Cullors: You know, in 2019, few years after or the year, I think after my book published, I was really thinking about what do I want to write about next? And I knew I wanted to write about Abolition next. I knew that felt important for me to talk to an audience, especially black folks, about the role abolitionist movements have played in our lives and that we’re living in a current moment in the current system that has primarily relied on the police, primarily relied on prison system to deal with poverty, to deal with mental illness, to deal with social ills, and that we needed something new. And that current system, the current system that exists, it doesn’t work for us. It doesn’t work for the majority of people who are living in this country. So, I wanted to create a handbook, something that can guide us, guide people. Starting with these steps, starting with my experiences, what I’ve seen, who I’ve talked to, talking about activists that people can learn from, and then going into these are the ways that you can continue to learn on your own, because our abolitionist journey is that it’s our own journey. We have to come to terms and grapple with it and then it felt important to close off the questions like, how are you going to continue doing this work? How are you going to think about doing this work? I really see this handbook as it’s not something you put on your shelf something that you put in your backpack or your purse, and you really can engage with the text, not just because it’s interesting information, but I’m interested in readers really being able to show up for the conversation and their lives around abolition. How do you practice it every day?

MN: Right. Yeah. I like how those guiding questions trouble the reader with how you’re going to do it in your own individual way. So, that was very clever to put us to task like that many people I’m not going to speak for everybody or broad stroke when I say this, but some people, I imagine, will think pre-civil war abolition when we hear the word you’ve brought this word. Not that it’s been absent throughout history or throughout time, but I feel like you’ve brought this word back into the forefront into these contemporary times. How does the word work today?

Yeah. And thank you for noticing that. I mean, yes, this word abolition or abolitionist or abolitionism or the concept of the abolitionist movement will probably make people think about the abolition of chattel slavery, the abolition of human beings being property. And that’s true. This movement, this modern-day abolitionist movement is actually a part of the legacy of the abolitionist movement to stop chattel slavery. But the problem is that we didn’t actually fully stop chattel slavery.

And most people know Ava Duvernay did an amazing job at lifting up the 13th Amendment. That was, yes, slavery. We’re done with it, except if you’ve been convicted of a crime. And then we get years and decades of laws created to criminalize black people’s everyday lives, whether that was lawyering laws. Right. So black people are no longer enslaved, but they’re not skilled workers. What are they supposed to do? So many folks are hanging out, and then you get loitering laws, the black codes, Jim Crow, and now we have mandatory minimums and gang injunctions. And so, we’ve morphed into this need to have a modern-day abolitionist movement. But it’s important for people to understand that the concept of abolition isn’t just about the police and prison system. What I’m trying to do with this book is I’m also trying to say that abolition is about building a new culture. How do we show up for each other? How do we treat each other? And we’re living in vicious times, not just at the systemic level, but how many times have you gone on social media where people are tearing each other down and treating people awful and not giving people the benefit of the doubt or there is this (inaudible) reaction to critique and blame and shame and point fingers. And I’m really asking for us to hold on, slow down and look at what is around us, and how do we build a new culture, a culture of care, a culture of dignity. So that feels important in this abolish culture as well.

MN: I feel like I sense that as I was flipping through the pages like this is soft. It’s accessible. It’s not asking me to be angry about anything or to run out and cut people off at the knees in order to get what we need as a people. I definitely sense that throughout the text, you answered the question of who this book is for. It’s for anybody who is fighting for will not to be oppressed and fighting for others. And you mentioned fighting against being caged. That was one of the words you use. Who is this book not for?

Oh, that’s a good question. I don’t think I’ve been asked that. I think it’s not for the person who’s unwilling to listen. I don’t think this book is for the person who is unwilling to hear why we should be showing up for each other with care and dignity, why we should be present for each other, why the current policing and imprisonment system has actually decimated whole communities. That’s fact now we have the numbers of how Black people, Brown people in poverty have been impacted by that system and I think that that’s important. If you’re going to read this book, if you’re going to show up for the text, you have to be open, you have to be ready, you have to be willing.

MN: Yeah, and you talked about imagination, right? Imagining this new place where we’re willing and doing the work of abolishing systems. So, I’m curious at if there’s a blueprint for that imagination. Is there something theoretical in place or something that is in practice, like what your book is doing? Is there something in practice that begins to really map out how we move in this world without being policed, without being incarcerated?

That’s a really good question. A good way to frame the question, too. One thing that I often do when people are questioning abolition is I ask people before you question, before you go down a long litany of criticism or I don’t know how we could do this. First, start with how could this be possible? What would make abolition possible? What would we need in place? What would you need in place? So many cities, Counties, States right now are dealing with the expansion of jails in their neighborhoods. The sheriffs are coming with a supervisor saying, oh, we need more jails or so many cities are watching it, right? Being like, well, crimes up. We got to put all this money back into the police. We have to pour money into the police. My question for all of us, for every single one of us, whether you don’t believe in abolition or you’re on the fence about it or you are an abolitionist, what would you do with those dollars? What would you do with those resources? We have to imagine something. We have to imagine something big and different. We have to think about what are other countries doing?

Are all countries have the same level of policing and imprisonment like us. They don’t. Does that mean that our country just happens to be has more crime and violence? Not necessarily. But what’s impacting people’s ability to really envision something different? I think a lot about part of imagining is just saying, like, do we all agree that people should have access to food, water, housing, employment or money? I believe we all believe that, right. We all believe that human beings need that. But not everybody has access to that. And why do we have access to policing and imprisonment? First? And truly, this comes from the culture that I’m calling carceral culture. Right. We live in a culture of punishment, vengeance and revenge. That’s culture that we live in, that’s what gets promoted. Right. I say something in the book, where online in particular, it’s the most wittiest, cruelest, meanest person who gets the most likes, who could be the meanest, who gets about the worst things about somebody, no matter the cost of them, themselves and other people, because we live in a culture of punishment that comes from a carceral culture. So, with abolition, we got to really dig in and decide, do we want to be in an economy of punishment or do we want to be in an economy of care? Do we want to have a culture of care?

MN: Right, I like that word care. And I’d be remiss if I did not bring up Adrienne Marie Brown, who has written Your Four Word, and she’s also the author of Pleasure Activism. And so, you being a person who cares for the world. Right. Cares for the people around you, cares for the work that you do. How do you step back and care for yourself?

I love this. Only Black women ask me this question. I know because we’re all trying to ask that question for ourselves. But I always love when a Black woman asks me this question so many ways, some of which have been weaponized against me from the right and from others, I choose my time wisely. There was a time where I would work 18 to 20 hours days, where all I would do was work, go to sleep, wake up and work. And then I had a child, I became a mom. I had to really shift. Like, what kind of life do I want my what do I want my kid to see? Firstly, I spend a lot of time with my child, but also, what do I want him to see from me? What kind of work habits do I want him to see? I love spending time with my community and friends, with people who make me happy, who see me, who know me for who I am that’s so important to me. And just a lot of like healing. A lot of healing and love and connection. Have a therapist who I love and has been such a critical container for me and these last I’ve been with her for four years now and I love us.

MN: So, like I said, I got questions. I got questions. Particularly around step number eight. Okay. Accountability, it’s a hard thing. And I’m speaking for myself. Right. It’s a hard thing to wrap our heads around. And you speak about it, you get into it. And I’m always curious about why that is difficult, even at the moment where I have to hold myself accountable. Why do you think accountability is so difficult?

I think it’s so difficult because we don’t live in a culture that practices centered accountability. I’m going to give you an example of what I mean by centered accountability. We’re taught as black women to be over accountable, which means that we have to hold the weight for everybody. We have to make sure the country is fixed. We have to make sure our families are fixed. We have to make sure we’re fixed. We literally have to hold the weight for everybody that is over accountability. And that doesn’t actually get us our needs met often means that we’re sacrificed highest numbers of autoimmune diseases are in Black women. Our nervous systems are often impacted because we aren’t getting our needs, that we’re treating everybody else’s needs without taking care of ourselves. And we are often not cared for. So that’s over accountability. Under accountability is what mostly white folks, our government. That’s under accountability. Right. So, we get the new Democratic Party in office because we had to make sure we get a fascist out of office and white supremacist. And now they accountable to us at all. We got them into office, and now they’re talking about give more money to police and not really investing in what Black people have talked about for the last multiple years. That’s under accountability. Centered accountability is when you hear somebody or you hear yourself say, hey, that was not acceptable. That didn’t work out well and now I’m going to say, sorry, I’m going to apologize. Most importantly, in accountability, you change your behavior. This doesn’t mean that you’re accountable to everybody and that’s tricky. Especially, I think, for many of us who are public figures or people see us a lot and feel like they know us, that we have to say yes to everything that they’re doing or say sorry for everything that we’re doing. That’s not what I’m saying. I’m accountable to the people who are accountable to me. I’m accountable to the people who are around me and are centered around me. And that is accountability that I’m really interested in. Accountability that’s mutual. That a mutual respect. An accountability that’s not about punishing me, but an accountability that’s making me stronger. Because if I’m stronger, you’re stronger and we are stronger.

MN: Right! That’s a word what you mentioned about being accountable to everybody, because I think when you get in a space of wanting to be a better person, you just throw yourself at the altar. Right. Let me care for everybody. But then I think that’s the form of self-harm as well.

I’ve been victim to that. I want to be really clear. I am a victim to I want to be available to everybody. That has caused me harm. I love that you cause self-harm because it has and so it’s a tricky road. But that’s why this work of abolition is about practice.

MN: So, I want to talk about accountability, just a smidgen, before we wrap up, you talked about the meanness of social media and yourself bearing the brunt of some of that, right, through media in general. And everybody wants to get the stories right. Who can grab the story, make it sensational myself as a journalist too. How or what do you need for Black media to do better by you?

I’m going to cry. You’re the first black journalist to ask that question. The single thing that I need from Black media for me, which also means for black women leaders like me, is before you republish something that’s often from right wing media, come ask questions. Come see if it’s true. Come check the sources. Some of the most painful attacks on me in this last ten months. It wasn’t right-wing media. I know what they do. That’s what they do. But it was when I watched Black media reappropriate the right-wing media stories and I was like, why didn’t you just come ask, ask the source or ask the sources around the source? So that’s seriously, like, the single most necessary thing I think Black media can do.

MN: Thank you. And like I said, I wanted to start and be accountable in the moment and having the information helps, right? I heard it say that the people who do not care for you cannot care for you and that hit me in the heart. And I just want to thank you for caring, for us. But before I let you go, before I let you go, I need you to give me your top five. And so, I thought about asking about the activist, but I’m seeing you’re an avid reader, so why don’t you give me your top five authors?

Okay. Darnell Moore, Alicia Garza, Octavia Butler, adrienne maree brown and Marge Piercy.

MN: Marge, thank you. I appreciate you. I appreciate you so much for sitting with us.

This is so special. Thank you. I really loved. I feel really cared for. So, thank you, team.