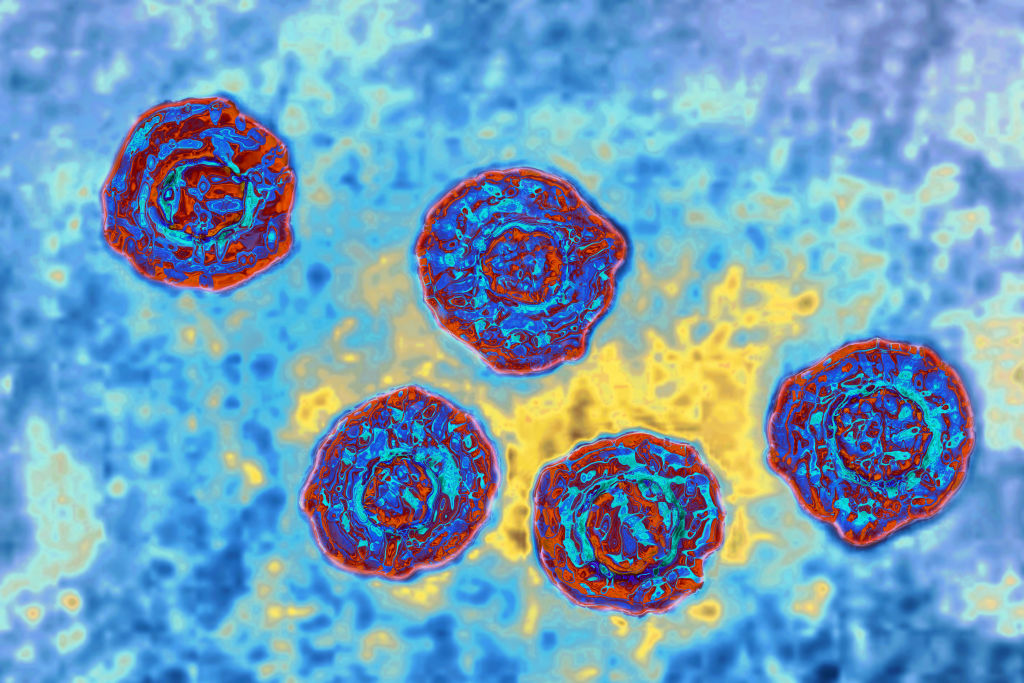

The hepatitis C virus. | Source: BSIP / Getty

Originally published on News One

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought conversations surrounding racial inequities in healthcare to the forefront. In its shadow lies a longstanding health issue that has disproportionately plagued communities of color for decades: hepatitis C. Behind the harrowing statistics are stories that illustrate the virus’ detrimental disparities.

We chatted with Louisiana-based physician Dr. Gia Tyson—a board-certified gastroenterologist at Ochsner Health who is part of the Louisiana Department of Health’s initiative to eliminate hepatitis C—to give us insight into the facts. Check out the interview below.

NewsOne: Black people are twice as likely to be infected with hepatitis C in comparison to the general U.S. population. They’re also twice as likely to die from hepatitis C than white people. What are the root causes behind its disproportionate impact on the Black community?

Dr. Gia Tyson: It goes back to social determinants of health. We realize health outcomes—especially in Black communities—really are affected by those social determinants like poverty. hepatitis C is transmitted primarily from blood-to-blood contact. There’s a higher risk with injection drug use. If that is prevalent in the community and there aren’t opportunities for harm reduction like needle sharing programs or people being treated for Hep C to get it out of the circulation, then those populations—especially African Americans—will be at higher risk of getting hepatitis C.

Separate from poverty, we know with race in and of itself, there are differences in how people are able to interact with the healthcare system. They may have limited access based on race alone and we’ve seen that with hepatitis C. There has been a gatekeeper energy around hepatitis C in terms of who can get treated and who can’t. That’s in the hands of physicians and we know that sometimes physicians can be biased so they may not be inclined to treat people with hepatitis C who are Black. There was a time when hepatitis C medications weren’t as effective in African Americans—that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t have been treated—but some providers may have taken that information and decided not to pursue treatment. There may have been African Americans who knew that the treatments were quite tough to get through and therefore didn’t want to be treated. In this era of new medication for hepatitis C, there is no difference in response to treatment based on race or ethnicity. Black people can get cured as easily as white people, but these old narratives may still be out there.

Washington, D.C. law requires girls to be vaccinated for HPV (a form of hepatitis). Photo taken on August 20, 2009. | Source: The Washington Post / Getty

NewsOne: Hepatitis C is one of the leading causes of death among Black people aged 45 to 65. Can you explain why those within that age group are at higher risk?

Dr. Gia Tyson: What we found was that risk-based testing for hepatitis C was not effective. All of our big public health organizations identified that at least 10 years ago. When we screen just based on risk factors including history of injection drug use, blood transfusions before 1992, and tattoos in unregulated environments, those types of risk factors were not getting enough people diagnosed. We also identified nearly 75% of those with hepatitis C were born between 1945 and 1955 compared to other age groups. It could be because some of those individuals had risk factors but didn’t acknowledge them because there is so much stigma around hepatitis C and its connection to drug use. We also know within that age group Black women who required blood transfusions during childbirth may have been impacted because the blood wasn’t being screened for hepatitis C before 1992.

There are a variety of reasons in terms of exposure risk. It’s challenging because if people aren’t in regular healthcare, hepatitis C can be a silent killer. It usually takes 20 to 30 years, in most people, of exposure to then develop Cirrhosis and have complications like liver cancer, liver failure and the need for a transplant.

NewsOne: Studies show 1 in 7 Black men in their 50s is living with chronic hepatitis C. Can you share insight into the impact that hepatitis C has on Black men specifically?

Dr. Gia Tyson: There is a difference in risk factors. We know in general hepatitis C is more prevalent amongst men compared to women and that may be tied to the risk factors in terms of blood-to-blood contact with injection drug use, tattoos, substance abuse and incarcerated populations. All of those risk factors tend to be higher in men than women. Males are more likely to be involved in those activities and therefore the prevalence of hepatitis C tends to be higher in men.

NewsOne: Studies revealed Black people are 18% less likely to access hepatitis C treatment than white people. Can you discuss the socioeconomic disparities surrounding access to treatment? How can we change the narrative?

Dr. Gia Tyson: When you take issues around poverty, access to health insurance, access to medical care and the changes in the hepatitis C landscape, this may be a reason why more African Americans are living with hepatitis C than our white counterparts. It also certainly contributes to why we die more from hepatitis C because if you’re not treated, don’t have access to treatment or are not offered treatment, then you’re more likely to have the worst outcome as it relates to developing cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, liver failure, the need for transplantation and then ultimately death related to hepatitis C infection.

When you’re in poorer communities, there may be issues around lack of access to insurance or folks may be on Medicaid and treatment for hepatitis C has been varied based on Medicaid in different states. Access has not always been the same, it has not always been equal. Depending on where you live, there may be more restrictions surrounding access to treatment. It also goes back to those social determinants of health. Many people can’t get a ride to the clinics, they have financial issues and they have pressing problems where they can’t take off from their jobs.

I’m very proud to say in Louisiana we’re one of the first states through our Louisiana Department of Health to put forth a statewide initiative to eliminate some of these barriers to treatment and disparities that exist. If we get people treated then we should eliminate the progression of fibrosis, the development of Cirrhosis, liver cancer and liver failure.

Source: Frank Bienewald / Getty

NewsOne: Research shows Black people with hepatitis C are twice as likely to develop bile duct and liver cancer than white people with hepatitis C. Can you share insight regarding the correlation between hepatitis C and liver and bile duct cancer?

Dr. Gia Tyson: The biggest pathway is through Cirrhosis. If someone has hepatitis C and they’ve had it for years or decades unknowingly, they may progress in terms of getting fibrosis or scarring in the liver. That fibrosis can escalate to fibrosis stage 4, and stage 4 is Cirrhosis of the liver. Cirrhosis is what really increases your risk of having primary liver cancer which includes hepatocellular carcinoma—which is the most common primary liver cancer—and cholangiocarcinoma which is bile duct cancer.

Everyone with Cirrhosis should be screened for liver cancer. Anyone with Cirrhosis should be getting an ultrasound with or without a tumor marker that we call an AFP every six months to be screened for liver cancer. The challenge in the African American community is that if we’re not getting regular medical care, then we’re not getting screened and therefore are more likely to present later during an advanced stage of cancer. That leads to poorer outcomes and a higher risk of dying because it’s less likely to be curable if you’re presenting at an advanced stage.

NewsOne: What are some ways to prevent its progression? How can someone take control of their health narrative?

Dr. Gia Tyson: The best way to take control is to be screened for hepatitis C. It’s important for us as Black people to take control and authority over our health because there can be so much bias and discrimination within the system whether you have access to insurance or not. The first step is knowing that everyone who is an adult should be screened for hepatitis C one time regardless of risk factors. There are still a lot of primary providers who don’t know that. If you’re an adult, 18 or older, your doctor should check you at least one time for hepatitis C. If you’re diagnosed, everyone should know there is a cure for hepatitis C. New medication called the direct-acting antivirals have a 98% chance of curing just about everybody whether you’ve been treated before and failed treatment, whether your cirrhotic or not cirrhotic and regardless of race.

NewsOne: Can you talk about the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists’ mission?

Dr. Gia Tyson: We know that even in 2022 there are still significant disparities as it relates to African Americans and our health issues in terms of getting diagnosed and treated. We also know there are still disparities and challenges as it relates to the workforce of African Americans in healthcare. When we look at specialist roles like gastroenterologists and hepatologists there are fewer African Americans who are in these positions. I joined the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists because they’re committed to addressing these issues. Their work is so important because it underscores the need for change at the patient and provider levels.

SEE ALSO:

Hepatitis C: What African Americans Need To Know About The Liver Disease

My Brother’s Keeper: Black Communities Need To Speak More Openly About Their Health