Source: frican American Policy Forum, / AAFP

In October 1984, 66-year-old Eleanor Bumpurs contacted her housing authority manager to explain she would be withholding her rent because people reportedly had “come through her windows, the walls, floors and had ripped her off.” A few days later, maintenance employees were sent to review her apartment and found no problems, except for cans of human feces in the bathtub, for which Bumpurs reportedly blamed, “Reagan and his people.”

After an inspection of her apartment, housing officials sent a city psychiatrist to visit Bumpurs who declared her “psychotic,” and “unfit to manage her affairs solely,” and ultimately recommended she be hospitalized. Social security services felt that the best way to help Bumpurs was to evict her before hospitalizing her.

On Oct. 29, as authorities arrived to evict Bumpurs, she resisted and made hostile threats. When the NYPD Emergency Service (a unit specifically trained to subdue emotionally disturbed persons), was unable to make contact with Bumpurs, police drilled the door lock, knocked it down and entered to find Bumpurs naked and holding a 10-inch knife.

When Officer Stephen Sullivan tried to restrain Bumpurs, she fought free. Sullivan then fired his 12-gauge shotgun, one hitting her in the chest, and killing her.

The killing of Eleanor Bumpurs was one of the earliest documented and racially charged cases in the 1980s that heightened racial tensions among African Americans and police. And while the Bumpurs case brought awareness to fatal assaults and deaths of African Americans while in police custody, and new alternatives to the use of firearms were introduced such as tasers, the unsaying narrative of Eleanor Bumpurs and many fallen Black women alike were deeply marginalized from mainstream discourse.

Until now.

Sonji Taylor, 27,  — killed by police Dec. 16, 1993

Tyisha Miller, 19, — killed by police Dec. 28, 1998

LaTanya Haggerty, 26, — killed by police June 4, 1999

In 2014, Eric Garner, Michael Brown and Tamir Rice were all tragically killed by police. America’s lack of urgency (during this period), to recognize police brutality among African Americans presented a crisis within a crisis. However, Black Lives Matter lifted their names in a movement that highlighted the racism, discrimination and inequality of police brutality against African Americans— specifically among Black men.

While Black people unjustly killed by police are more than names, Black women like Kimberlé Crenshaw knew it was still crucial for all those names to be spoken. And more urgently, while Black men like Garner, Brown and Rice were being killed at alarmingly high rates, Black women like Michelle Cusseaux, Tanisha Anderson and Pearlie Golden, were being killed by police, too.

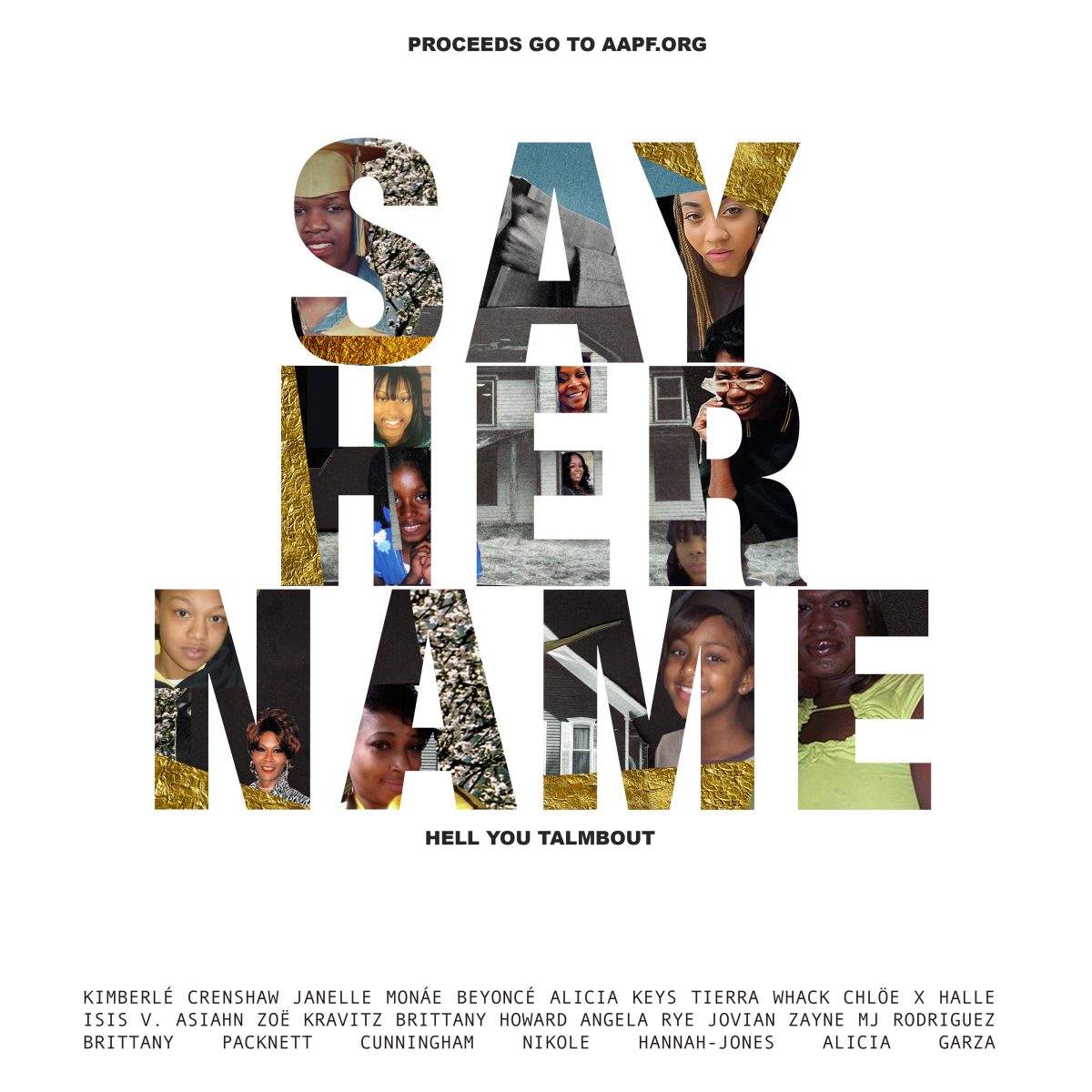

As a result, in December 2014, the African American Policy Forum (AAPF), launched the #SayHerName campaign, a social movement seeking to raise awareness for Black female victims of police brutality and violence. For the past eight years, #SayHerName has added power to Black Lives Matter and commemorated Black women who lost their lives to police brutality and violence in America.

Kendra James, 21, — killed by police May 5, 2003

Kathryn Johnston, 92, — killed by police Nov. 21, 2006

Aiyana Stanley-Jones, 7, — killed by police May 16, 2010

The story begins with intersectionality.

In 1987, Kimberlé Crenshaw, a Black feminist scholar and civil rights advocate, was in college writing seminal papers for the University of Chicago, when she realized the misconception regarding Black women and how the gender aspect of race relations was largely underdeveloped in academia and society. This observation would inform Crenshaw’s focus on Black women’s overlapping forms of discrimination; often leaving us without the fairness necessary to equitably expand in America.

Between 1989 and 1991, Crenshaw’s two essays: Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex and Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color became advocates for the unsaid narrative around Black women’s gender and race issues.

Intersectionality, coined by Crenshaw, challenged general notions about the experiences of women and provided a framework that demonstrates discrimination against Black women is more complicated than misogyny and racism. The concept of intersectionality has catapulted to mainstream discourse in regard to identity politics, justice and police brutality.

Rekia Boyd, 22, — killed by police March 21, 2012

Renisha McBride, 19, — killed by police Nov. 2, 2013

Sandra Bland, 28, — killed in police custody July 13, 2015

In 2013, Black Lives Matter was formed by three Black female activists, Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi, via social media hashtag after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. The movement thereafter became a social-political action committee aimed at highlighting racism, discrimination and racial inequality experienced by African Americans.

By 2014, Black Lives Matter had shifted from a social media hashtag to national headlines, specifically after the police shooting deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York City. While the movement’s mission was founded on an awareness of the brutal experiences of all African Americans, Black Lives Matter at most, centered awareness around the police brutality against Black men, which left Black women’s similar experiences sidelined.

“Say Her Name sheds light on Black women’s experiences of police violence in an effort to support a gender-inclusive approach to racial justice that centers all Black lives equally.” — Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women, December 2014

In an effort to create a mainstream social media presence alongside Black Lives Matter, Crenshaw in conjunction with the African American Policy Forum (AAPF), coined #SayHerName in December 2014. The year 2014 marked the unjust police killings of a number of Black women such as Gabriella Nevarez, Aura Rosser, Michelle Cusseaux and Tanisha Anderson.

As the list of Black women killed by police rose after 2015, so did the lack of acknowledgment and accountability for their deaths.

Natasha McKenna, 37, — killed in police custody Feb. 8, 2015

Meagan Hockaday, 26, — killed by police March 28, 2015

Kindra Chapman, 18, — killed in police custody July 14, 2015 (the day after Sandra Bland was also found dead in police custody)

Sandra Bland was a 28-year-old African American woman from Chicago, Illinois. She was one of five sisters, one of many students to attend and graduate college and one of many to challenge and address police mistreatment of African Americans.

“If all lives mattered, would there need to be a hashtag for Black Lives Matter?”

Sandra Bland was one of many — and more devastatingly — Black women to suffer such police mistreatment and die in their custody.

On July 10, 2015, Bland was pulled over after failing to signal a lane change, and after a heated interaction with Officer Brian Encinia, Bland was pulled from her car, forced to the ground and arrested. Bland was charged with assaulting a police officer and placed in a jail cell alone because she was deemed a high risk to others. “How did switching lanes with no signal turn into all of this?” Sandra asked in a voice message to her friend.

Three days later, on the morning of July 13, Bland was discovered dead in a semi-standing position hanging from her cell.

Following Bland’s death, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Andrea Ritchie, the AAPF and The Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies released an updated version of the 2014 Say Her Name report. The updated report helped inform the tragic circumstances around Bland’s death as well as reignited conversations regarding police brutality and killings of Black women.

Atatiana Jefferson, 28, — killed by police Oct. 12, 2019

Breonna Taylor, 26, — killed by police March 13, 2020

Priscilla Slater, 38, — killed in police custody June 10, 2020

Not only do the social, political and justice movements from history to the present largely overlook the contributions of Black women, but they also fail to address fatal contributing factors specific to Black women. Thankfully, #SayHerName has become a social-political phenomenon addressing the intersectionality of how gender, race and class violently impact Black women and girls worldwide.

While the updated 2015 Say Her Name report highlighted the events surrounding Sandra Bland’s death and commemorated more Black women who’d been tragically killed by police or in police custody, the report also detailed incidents from the past three decades of Black women’s fatal encounters with police brutality and violence (including the shooting death of Eleanor Bumpurs), and several recommendations for how people at every level; activists, researchers and policymakers, can best address and advocate equitable rights for Black women victims.

Some demands included:

- Holding police accountable for violence against Black women and girls.

- Creating and passing reforms that specifically address the home as a site of police violence against Black women.

- Ending the use of no-knock warrants.

- Investing in forms of community safety and security that do not rely on police officers.

With such awareness around victimized Black women, like Breonna Taylor, who was killed by police in March 2020, #SayHerName’s demand for policymakers was in some measure answered. Six years after Say Her Name’s call to action and a year after Taylor’s death, the City of Louisville officially banned no-knock warrants in April 2021 and named it “Breonna’s Law.”

By addressing the incidents of police violence against Black women, too, #SayHerName captured the full racial demographic of those most directly impacted by police killings, incorporating Black women’s experiences with brutality and anti-Black violence into mainstream racial justice narratives, while also commemorating Black women who’ve tragically lost their lives to police brutality and violence.

More importantly, the movement has become a light for the unseen Black women who are often marginalized in mainstream discourse and society.

Since the movement’s inception in 2014, #SayHerName has held two national events (in San Francisco and New York), to increase awareness around brutal violence against Black women. Also, Crenshaw and the African American Policy Forum organized and sponsored #SayHerName: A Vigil in Remembrance of Black Women and Girls Killed by the Police in May 2015 and the Mother’s Network in November 2016, to aid families who’ve lost Black women to police violence.

In a herstorical approach, #SayHerName has risen to its counterparts of racial violence discussion and has aimed not to replace Black Lives Matter,  but to integrate Black women into the conversation and perspectives of racial injustice.

As we commemorate the movement on its eight-year anniversary, we hope that it may continue to serve as a pillar in the Black female community and a vital resource to community organizers, media, policymakers and others invested in dismantling racial injustice. Because the continuation of marginalizing violence against Black women and girls cannot be the solution to drive out their darkness of brutality and death.

Only more lights like #SayHerName can do that.

RELATED CONTENT: ‘Say Her Name’ Initiative Partners With Producers Of Korryn Gaines’ Documentary To Tell Her Story