Courtesy of Raven Wilkinson

As history will tell you, it’s not easy being the first person to do anything. And for Raven Wilkinson, the very first ballerina to sign a contract to join a major dance company in the United States, it was anything but a cake walk. It took three auditions, after being rejected twice, for the gifted ballerina to be invited to perform with the prestigious Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. And when she traveled with the group, she was met with resistance on stage, while riding down South with her troupe, and even while trying to check into hotels with them, all because she was a Black woman. And despite her fair complexion, Wilkinson never tried to hide the fact that she was Black, providing her with even more obstacles along the way.

But the struggles she endured, to her, were worth it. “We are a strong people,” she told us over the phone. “There is no reason for us to ever be ashamed of anything. We have held up this country. It would have fallen in many of a time if we hadn’t been there holding it up with our strength and our belief in it.”

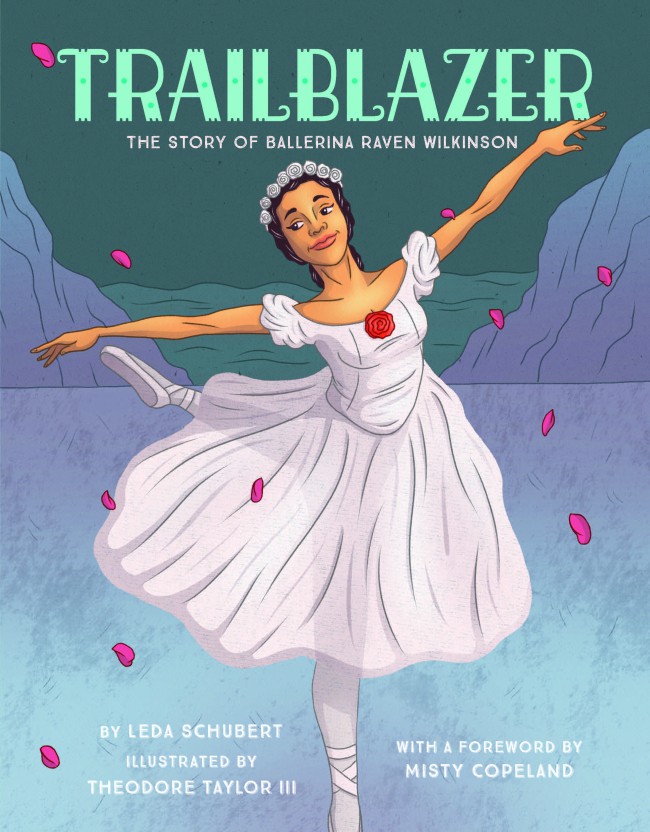

The hurdles she would have to get over would open doors for today’s ballerinas to be able to reach the greatest of heights. That includes a one Misty Copeland, whom Wilkinson is a proud mentor of. That will also include another generation of future dancers, who can read about Wilkinson’s story in the new children’s book based on her life, Trailblazer: The Story of Ballerina Raven Wilkinson. The beautiful picture book by Leda Schubert, with illustrations by Theodore Taylor III, takes us through her journey of watching the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo as a kid and being inspired, to performing for the famed company as an adult. Through the book, we learn so much about her and a career that has lasted much longer than the detractors she met up with in the ’50s and ’60s ever could have imagined. Learn more about her story through our chat with the legendary dancer below.

MadameNoire: Why was it so important for you to push past the nos with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, keep auditioning, and prove that your talent was far greater than any concerns people might have about your skin color?

Raven Wilkinson: You put it in words yourself. That’s the greatest way to put it I’ve ever heard. I think you realize that the hate is such a waste. It’s so full of hot air. It’s so meaningless. And even though you know the realities of life because you were born into this system and I lived with it all of those years, I felt they didn’t matter to me. To pursue the thing that gives you joy and is what you have a gift for is so much more than those negativities. You can’t let them form your life. You have to bat each one down and try to fight around it. You have to give it a try. Nobody said, “We’re sure that you’re going to win this,” but you have to at least give it a try. I was sure enough of myself, of wanting to dance so much, that this other stuff was so much hot air to me. The realities were there. But when I finally met them when we were on tour in the Southern states, they certainly were no surprise. I expected there would be some incidents. But the thing that got me and showed me something, which I always remembered, was the people I was traveling with in the company who were so shocked and hurt. They knew mentally what we know emotionally as African Americans. They knew something in their minds. They knew about Jim Crow and segregation. But it’s when they met it personally themselves through a member of their group and one of their colleagues and friends that you could see the shock and hurt and pain in their faces. That almost made me feel worse [laughs]. But that’s a good lesson to learn. Because people don’t always understand it, the actual feeling of it, until they experience it.

Raven and her family — Courtesy of Raven Wilkinson

According to the book, one of your first ballet teachers asked you if you were French or Spanish. Being that you are of a lighter complexion, did you ever consider “passing” to avoid trouble while on the road dancing?

No, I didn’t. Because, I mean, certainly the idea comes up in front of you in your mind if you want to try that course. But to me, it felt like I had to disown myself in order to do that. And I just felt that I couldn’t do that. I felt getting out there and dancing on stage was a presentation of your soul. And if I couldn’t look at my soul and be secure in who and what I was, then how could I say it on stage with my body while dancing? Dancing is such an intimate way of performing because it’s the total machinery of your soul, your mind, your body, all at work. In New York, if you were above 110th Street, that was Harlem. That’s where we always had to be. I grew up in the ’40. I was born in 1935. When I would go downtown to Fifth Avenue, when I went with my mother, people would ask what we were because they noticed we were different. They thought maybe we were foreign or something. My mother always would say, “I’m American. We’re Americans.” And then they would want to know a little more so they would pry and she would say, “We are Americans. We are born here.” They would sort of give up, but I knew what they were asking. So I had no trouble when I was growing up and someone would say “Can I ask you a question?” I told them! And in those days you were called “colored.” You weren’t called “Black.” So I would tell people when they would ask me that question of “Where are you from?,” “‘I’m from New York.” I would say, “I’m colored.” I would see them having to go through all these changes to readjust and figure out what box to put you in and label you as. I saw them going through all these difficulties and I thought, “That’s not my problem. It’s their problem, not mine.” I wanted to live my life fully without a problem and it was no reason for me not to. And I’m so glad because I do have family who passed and it’s an unending thing. You have to sort of separate yourself from your family, and if you don’t, there’s always that feeling that members who didn’t go that route would have to protect you. Oh, it’s a mess! And I knew I wouldn’t live that way. There’s no reason to have to live that way. I don’t think a little bit of indecency in life you have to meet up with because of your race compares to the indecency you have to put yourself through to pass. But I think people need to have the room to make decisions about themselves and their life as they want to. I would never tell anybody else to do this or do that.

So it’s true that you were very open about the fact that you were Black. How did that work when you would have to go down South?

The South had begun to really act up because of the desegregation of the schools. So when we rolled up into that hotel in Atlanta, and we were all in line to get our rooms at the hotel, I saw this man in a business suit talking with my manager of Ballet Russe and an African-American woman in uniform who ran the elevator. And when I was talking to Mr. Daniver in his office before this happened, I had told him, I wanted to be so much in Ballet Russe, but I just could not disguise myself. I had to be who and what I was and I just hoped it wouldn’t mean any danger for the company or any trouble. So he let me go ahead and try that. But these two years later, this thing was beginning to hit. So the man in the business suit at the hotel came up to me and he asked me to come out of the line and talk with him. He said he’d asked the manager of my company if there was a negro in my company. He said no. “But I asked the elevator operator if she’d seen anybody she thought would be a negro or might be and she pointed you out.” So I said, “Well yes, I am.” He said, “Well what are you doing here? You know you can’t stay here in this hotel.” It was against the law. So I said, “Well what would you do if I told you I’d stayed in this same hotel two years before and nothing happened?” He said, “Please don’t say that.” He said, “You don’t know how bad things are getting now. They could bomb my hotel in a minute.” So he called the colored taxi to take me to the colored hotel, and meanwhile, my roommate refused to let me go alone. She was saying, “I’m going with you. I don’t care.” Everybody was saying, “No, you can’t go, you have to stay.” And she said, “No, she’s not going alone, I’m going with her.” So finally I said, “You can’t go to a colored hotel just like I shouldn’t be in the white hotel so you have to stay here.” So that was that incident.

So with incidents like that, according to the book, you were big on your faith. How did you rely on that during trying moments like this and seeing burning crosses and hatred when you traveled down South?

I think I always had a sense of hope and a sense of — I just knew that this was a lot of ignorance, as prejudice is. It’s a lot of hot air. It’s a lot of ignorance, but it’s a very dangerous element in our society because it has ballooned. A balloon is full of air too and they expand and it’s very dangerous because they can eventually explode, or pop, in the end. So you always have to watch it. But I think I didn’t believe that it touched me personally. Let’s put it this way, I was riding through those states on a bus. Or if it got bad, they had to send me back to New York and I had to wait it out until it got in a better place. I remember very often rejoining the company in Baltimore. But going through a place in a bus is different from if you live there. My parents and family came from South Carolina, so they were Southern. I had visited with my relatives down there since the time of being a little girl, but you’re not so aware of things. For instance, I remember when I was a little girl visiting my grandmother in South Carolina, I was walking down the street in Orangeburg, South Carolina with some little friends I had made there. They had this playground with those merry-go-rounds you sit on and they go round and round. We didn’t have those in the North in New York. I was always fascinated to get on one of those little merry-go-rounds. So I ran on to the playground. It was empty and there were no other kids there. And this little huddle of the other little girls I was with stood on the sidewalk and watched me in horror. I said, “C’mon, let’s get on the merry-go-round!” They just stood there looking at me, eyes big. I said, “What’s wrong?” They said, “This is a white kid’s playground.” I said, “So what?” The only thing that made sense to me was riding the merry-go-round. So obviously, I was not brought up that way. I only passed through.

So I would say faith had a lot to do with everything I did. When I was disappointed I would just lay it there with faith and grace and usually I saw a way out of it.

Why did you want to share your story in a children’s book instead of going the traditional biography route?

It’s a simple story geared to kids ages six to nine. I think it’s a story that kids can see things in because kids have a deep-seated sense of reality and yet they have a very explosive imagination. And I think where the two meet in the middle is a good story to give to kids while being very careful. Leda Schubert submitted it to publishers who were cognizant of her work, but none of them them wanted to publish it. I don’t know this, but I only could think they felt some of it was too drastic for kids to think about. This was in 2009. But within the last few years, things have changed, Misty Copeland became a ballerina and people have talked about her being an African-American artist and the fact that we haven’t had any in ballet who’ve risen that far. So there comes the question of why is that? And how did that happen? People were beginning to question it. And young people, I think people are more open about what we tell them and how we answer them. We’re more truthful. We don’t try to hide much from them.

Getty

How did you come to be a mentor to Misty and why is that relationship so important to you?

Misty is on her own meteoric path, and she’s the next one to pick up the mantel of mentorship. Misty chose me. Years ago, I was doing something in the kitchen and the television was on. I heard something and ran in to look. They were showing this little girl, 13, out in California, doing this classical variation on pointe and like I’ve never seen before. They said she was African American and I said “What?!” She danced so beautifully. She had all that sense of movement and what a ballerina was and she was only 13. So already, that’s a talent. I had a feeling inside of me, this is the dancer and she’s going to break through. I just got on my knees and and prayed that her career would be allowed to advance and grow and develop, and sure enough, it did. As the years went on, I looked for her in ballet theater. It said she was going to the Ballet Theater School or that was her hope. And then people would say, “Yeah, she’s in that company.” Then I saw this thing on television that was advertising a season at the MET. It show showed her doing this famous dance from the first act of Giselle, and I said, “I’m going to see that!” So I went to see it and there was Misty. The minute she came on stage, it was like a breath of fresh air. What she has is a generosity of movement. She just brings the audience in with her. She has both a technique and a certain kind of charisma. And then her publicist got in touch with me, oh, six months to a year later and asked would I be interested in talking with her at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Like a little discussion about our experiences. I said “Oh, yes!” So that was the first time I met her and she rushed from rehearsal and I thought, “She must be so tired.” But this lovely young lady floated down the steps with peace and calm and she just called out my name. She said “Raven!” and we both embraced. It was the sweetest moment. We talked about our various experiences and that’s when she told me I was a mentor to her. That when she saw this documentary about the Ballet Russe Monte Carlo, the company I was in, she was so thrilled to know there had been a Black dancer in that company. I was thrilled to see her dance when she was 13 in that little documentary, and she felt, this is someone like me who has gone before and she’s somebody I want to know about. So it just sort of happened.

I don’t know that art or people or God you choose, I think they choose you. I think on the road to artistic fulfillment, only you can pass that road. No one else can have the experience for you. And so I always say, “I love to be the wind at your back anytime I can be.” She can only go through the experiences herself. She’s overcome so much in a very short life compared with my 83 years, and yet, she’s such a developed young woman in such a beautiful way. So I call Misty my mentor [laughs].

Trailblazer: The Story of Ballerina Raven Wilkinson is available on bookstands now.